52Specific practices are set forth below in Case-Level Leadership.

53The research around the impact of this specialization suggests that a specialized unit, in and of itself, will not improve prosecution rates unless the prosecutors are specially trained, aggressive, informed, and skilled trial attorneys, who understand that they need to measure performance by looking beyond conviction rates. See Beichner & Spohn, supra note 13. A complex world needs silos to create order out of complexity. Silos and discrete specialization are necessary to a functional society, but without integrating the silos, isolation of information can be self-limiting and reduce effective responses to issues. See also Gillian Tett, The Silo Effect: The Peril of Expertise and the Promise of Breaking Down Barriers, 14 (Simon & Schuster 2016).

54Sexual assault, domestic violence, child physical and sexual abuse, human trafficking, witness intimidation, and gang-related crimes (e.g., racketeering).

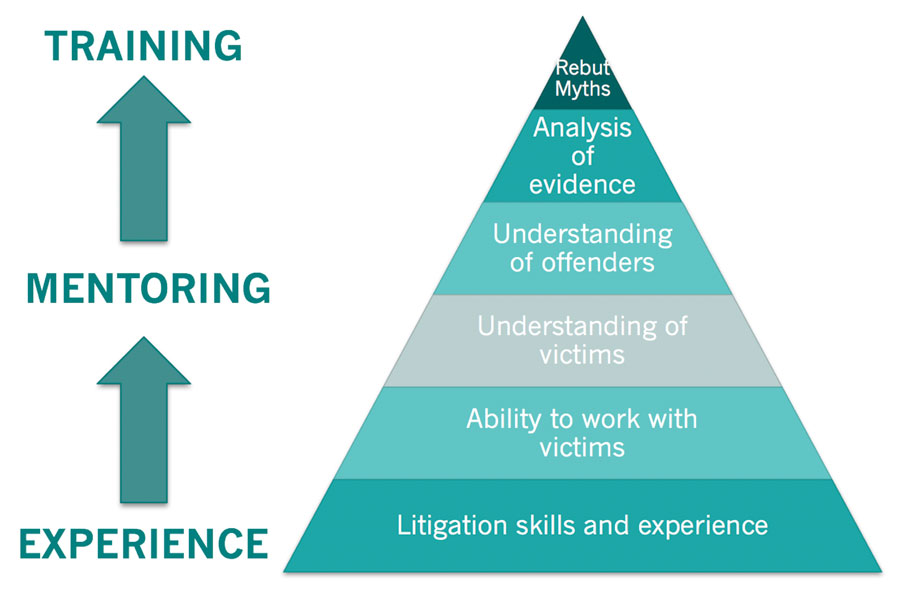

55 See, e.g., Domestic Violence, American Prosecutors Research Institute (1997); and Sean Mcleod, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Simply Psychology (2016), http://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html (last visited Apr. 10, 2017) (consider how the needs motivation fits into the necessary skills of prosecutor). For help integrating logical and scientific data into your prosecution practice at 202-558-0040 or info@aequitasresource.org.

56 See Appendix B. Core Competencies for Prosecuting Sexual Violence.

57Id.

58 For sample briefs, research, and review of motions and briefs, contact AEquitas at (202) 558-0040 or info@aequitasresource.org.

59 Contact AEquitas for guidance on integrating sociological and scientific data into your prosecution practice at 202-558-0040 or info@aequitasresource.org.

60 See Integrating a Trauma-Informed Response and Interviewing Victims in Appendix B for guidance on Core Competencies for Prosecuting Sexual Violence and further detail on training.

61 See, e.g. Sandra L. Bloom, Understanding the Impact of Sexual Assault: The Nature of Traumatic Experience, in Sexual Assault: Victimization Across The Lifespan 405-32 (A. Giardino, E. Datner & J. Asher, Eds., GW Medical Publishing 2003); Saba Masho & Anika Alvanzo, Help-Seeking Behaviors of Men Sexual Assault Survivors, 4(3) Am. J. Mes. Health 237-42 (Sept. 2010); and Kristiansson & Whitman-Barr, supra note 7.

62 See, e.g., Rebecca Campbell, The Neurobiology of Sexual Assault: Implications for First Responders in Law Enforcement, Prosecution and Victim Advocacy, National Institute of Justice (transcript) (Dec. 3, 2012), available at http://www.nij.gov/multimedia/presenter/presenter-campbell/pages/presenter-campbell-transcript.aspx [hereinafter The Neurobiology of Sexual Assault]; and Alifair S. Burke, Rational Actors, Self Defense, and Duress: Making Sense, Not Syndromes, Out of the Battered Woman, 81 N.C. L. Rev. 211 (2002).

63 See Teresa Scalzo, Prosecuting Alcohol-Facilitated Sexual Assault, Nat’l District Att’y Ass’n. (Aug. 2007); Antonia Abbey, et al., Alcohol and Sexual Assault, 25(1) Alcohol Res. & Health 43 (2001); and Antonia Abbey, et al., Review of Survey and Experimental Research that Examine the Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Men’s Sexual Aggression Perpetration, 15(4) Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 265-82 (Oct. 2014).

64 See AEquitas, Literature Review: Sexual Assault Justice Initiative (2017).

65 See Louis Ellison & Vanessa Munro, Complainant Credibility & General Expert Witness Testimony in Rape Trials: Exploring and Influencing Mock Juror Perceptions, Univ. Nottingham & Univ. Leeds, (2009); and Louise Ellison & Vanessa E. Munro, Reacting to Rape: Exploring Mock Jurors’ Assessments of Complainant Credibility, 49 Brit. J. Criminology 202 (2009).

66 For sources of specific research, see AEquitas, Sexual Assault Justice Initiative Annotated Bibliography (2017).

67 See Section 3.1-C. Making Charging Decisions Consistent with Research and Ethical Considerations.

68 American Bar Association, Model Rules of Professional Conduct, Preamble, available at: http://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/model_rules_of_professional_conduct_preamble_scope.html (“As a public citizen, a lawyer should seek improvement of the law, access to the legal system, the administration of justice and the quality of service rendered by the legal profession. As a member of a learned profession, a lawyer should cultivate knowledge of the law beyond its use for clients, employ that knowledge in reform of the law and work to strengthen legal education. In addition, a lawyer should further the public’s understanding of and confidence in the rule of law and the justice system because legal institutions in a constitutional democracy depend on popular participation and support to maintain their authority.”).

69 See Spohn, Beichner & Davis-Frenzel, supra note 10.

70 See Lisa Frohmann, Convictability and Discordant Locales: Reproducing Race, Class, and Gender Ideologies in Prosecutorial Decisionmaking, 31(3) L. & Soc’y Rev. (1997); and Jeffrey W. Spears & Cassia C. Spohn, The Genuine Victim and Prosecutorial Charging Decisions in Sexual Assault Cases, 20(2) Am. J. Crim. Just. (1996).

71 Michelle Madden Dempsey, Prosecuting Violence Against Women: Toward a “Merits-Based” Approach to Evidential Sufficiency, Vill. U. Sch. L. (2016) (citing Joanne Archambault & Kimberly Lonsway, The Justice Gap for Sexual Assault Cases: Future Directions for Research and Reform, 18 (145) Violence Against Women PAGES (2012). Much of the difficulty in securing reliable social science research can be attributed to the failure of police and prosecutors to maintain systematic records of cases reported.

72 Beichner & Spohn, supra note 13.

73 See Criminal Justice Standards, Prosecution Function (Am. Bar Ass’n, 4th ed. 2015), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/criminal_justice/standards/ProsecutionFunctionFourthEdition/.

74 See Nat’l District Att’y Assoc’n, supra note 36.

75 See Appendix I – Ethical Considerations.

76 See Dempsey, supra note 71.

77 See id.

78 “Vicarious trauma focuses on the cognitive schemas or core beliefs [of the person exposed to accounts of a victim’s trauma]… and the way in which these may change as a result of empathic engagement with the [victim] and exposure to the traumatic imagery presented by clients. This may cause a disruption in the therapist’s view of self, others, and the world in general.” Ted Bober & Cheryl Regher, Strategies for Reducing Secondary or Vicarious Trauma: Do They Work? available at: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/80997/1/Regehr%20strategies%20for%20reducing%20secondary%20or%20vicarious%20trauma.pdf (citing I.L. McCann & L. A. Pearlman Vicarious Traumatization: A Framework for Understanding the Psychological Effects of Working with Victims, 3(1) J. Traumatic Stress, 131–149 (1990). See also R. Sabin-Farrell & G. Turpin, Vicarious Traumatization: Implications For The Mental Health Of Health Workers? 23 Clinical Psych. Rev., 449–480 (2003).

79 Joyful Heart Foundation, Vicarious Trauma, http://www.joyfulheartfoundation.org/learn/vicarious-trauma.

80See Peter Jaffe, et al., Vicarious Trauma in Judges: The Personal Challenge of Dispensing Justice, 54(2) JUV. & FAM. CT. J. 6 (Fall, 2003) (“…exposure to the graphic evidence of human potential for cruelty exacts a high personal cost.”).

81 See Molly Wolf, et al., “We’re Civil Servants,” The Status of Trauma Informed Care in the Community, 40 J. Soc. Serv. Res. 111-120 (Dec. 12, 2013).

82 Joyful Heart, supra note 80. See also Tina Mattinson, Vicarious Trauma: The Silent Stressor, Inst. Ct. Mgmt. (May 2012), http://www.ncsc.org/~/media/files/pdf/education%20and%20careers/cedp%20papers/2012/vicarious%20trauma.ashx.

83 See Linda Albert, Keeping Legal Minds Intact: Mitigating Compassion Fatigue Among Government Attorneys, 20(1) Pass It On (Fall 2012), http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/pass_it_on/PIO_F12.authcheckdam.pdf. For staff training on addressing vicarious trauma, see Developing Resiliency and Addressing Vicarious Trauma in Your Organization, Office of Victims of Crime, Techn. and Training Assistance Ctr., https://www.ovcttac.gov/views/TrainingMaterials/dspCompassionFatigueTraining.cfm; and Vicarious Trauma Toolkit, Ne. U, Inst. on Urb. Health Res. and Prac. (Spring 2017), http://www.northeastern.edu/iuhrp/projects/current/vicarious-trauma-toolkit-vtt/.

84 Some jurisdictions may rotate prosecutors who are handling sexual violence cases to prevent burnout, but the practice poses a risk to consistent best response practices. Daring to Fail, First Person Stories of Criminal Justice Reform, Ctr. for Court Innovation (2010), http://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/Daring_2_Fail.pdf (“[w]hen departments rotate officers to keep things fresh and responsive, there’s a critical loss of institutional memory and momentum”). Prosecutors who consistently handle sexual violence cases will succeed more and see the impact of their work, not only in trial but in the system as a whole. They will become part of the coordinated team, will be sought out by team members and colleagues and will be able to engage the community more taking their role beyond the courtroom. Where rotation is necessary, the negative effects can be mitigated by staggering the timing of rotations and carefully selecting skilled and knowledgeable replacements.

85 See Laurie Anne Pearlman & Lisa McKay, Understanding & Addressing Vicarious Trauma, Headington Inst. 19-20 (2008), http://www.headington-institute.org/files/vtmoduletemplate2_ready_v2_85791.pdf; and Compassion Fatigue/Vicarious Trauma, Office for Victims of Crime Training and Technical Assistance Ctr., https://www.ovcttac.gov/views/TrainingMaterials/dspCompassionFatigueTraining.cfm (last visited Mar. 31, 2017).

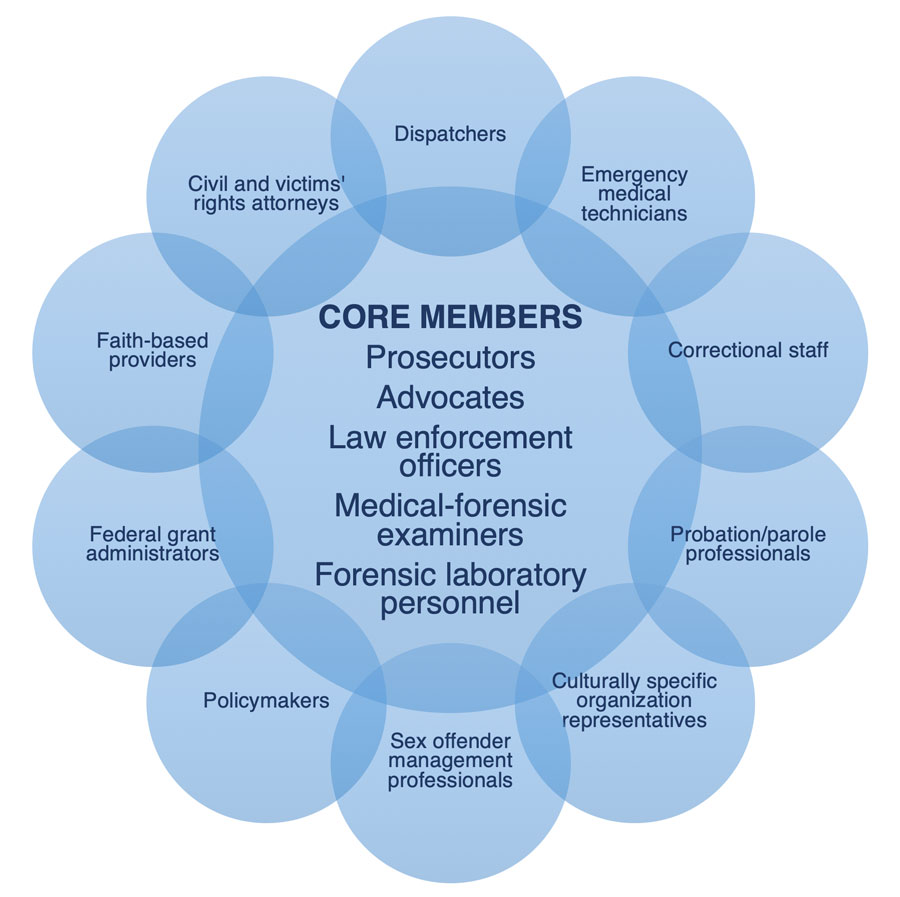

86 What is a SART? SART Toolkit, https://ovc.ncjrs.gov/sartkit/about/about-sart.html (last visited Mar. 4, 2017) (convening a sexual assault task force to discuss the potential formation of a SART/MDT is an initial step – it takes some time to discuss and agree upon MOUs and confidentiality agreements).

87 Rape Abuse Incest National Network (RAINN), What is a SANE/SART? available at https://www.rainn.org/articles/what-sanesart.

88 See AEquitas, Literature Review: Sexual Assault Justice Initiative (2017).

89 For various perspectives on SART development see AEquitas, Literature Review: Sexual Assault Justice Initiative (2017).

90 Some jurisdictions may refer to SANEs or to sexual assault forensic examiners (FNEs). For the purposes of this publication, the authors have used the term SANE.

91 See Rebecca Campbell, et al., Adolescent Sexual Assault Victims and the Legal System: Building Community Relationships to Improve Prosecution Rates, 50(1-2) Am. J. Community Psychol. 141-54 (2011); Rebecca Campbell et al., Prosecution of Adult Sexual Assault Cases: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Impact of a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner Program, 18(2) Violence Against Women 223-44 (2012); and AEquitas, Literature Review: Sexual Assault Justice Initiative (2017).

92 See Appendix D for further discussion of the components of SARTs and the roles and responsibilities of team members.

93 For more guidance on soliciting feedback to improve prosecution response, see RSVP Volume II, Chapter 9.

94 See, e.g., Todd Landman et. al, Code 8.7: Conference Report (United Nations U., 2019), available at https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:7313/UNU_Code8.7_Final.pdf. The Regional Intelligence and Investigative Center (RIIC) of Lehigh County, PA; along with Lehigh University, AEquitas, and The Why, is developing an artificial intelligence application to mining police report narratives to identify potential human trafficking victims and perpetrators.

95 See Violent Criminal Apprehension Program, Homicides and Sexual Assaults, Fed. Bureau of Investigations, https://www.fbi.gov/wanted/vicap/homicides-and-sexual-assaults (last visited June 15, 2017).

96 See Recording by Jane Anderson, #Guilty: Identifying, Preserving, and Presenting Digital Evidence, https://gcs-vimeo.akamaized.net/exp=1574288366~acl=%2A%2F884497848.mp4%2A~hmac=8361ca1a9ff292a8a9f27a73f97b89210542585ce5d16de8e5025788cf390dad/vimeo-prod-skyfire-std-us/01/2059/8/210299223/884497848.mp4 (recorded November 28, 2017).

97 See International Association of Chiefs of Police, Intelligence-Led Community Policing, Community Prosecution, and Community Partnerships, Cmty. Oriented Policing Servs., (2016) (study on community policing that provides insight into the assessment of police response, the necessity of working with community and criminal justice partners, and the importance of action steps to improve community safety).

98 See, e.g., Elaine Borakove, et al., From Silo to System: What Make a Criminal Justice System Operate Like a System? Justice Mgmt. Inst. (Apr. 2015), available at: http://www.safetyandjusticechallenge.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/From-Silo-to-System-30-APR-2015_FINAL.pdf; and Rolf Pendall, Can Federal Efforts Advance Federal and Local De-Siloing, Urban Inst., 2 (May 17, 2013), http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/23626/412820-Can-Federal-Efforts-Advance-Federal-and-Local-De-Siloing-Full-Report.PDF.

99 Tett, supra note 53 at 142.

100 Id.

101 See Megan R. Greeson & Rebecca Campbell, Sexual Assault Response Teams (SARTs): An Empirical Review of Their Effectiveness and Challenges to Successful Implementation, 14(2) Trauma Violence Abuse 83-95, 84 (Dec. 2012).

102 Cases may also be multijurisdictional (e.g., Indian Country where there can be concurrent tribal/federal jurisdiction).

103 See Pendall, supra note 98.

104 See, e.g., id. at 20.

105 Sexual Violence, Women’s Law Project, http://www.womenslawproject.org/sexual-violence/ (last visited May 22, 2017); see also Women’s Law Project, Advocacy to Improve Police Response to Sex Crimes, Policy Brief (Feb. 2013), http://www.womenslawproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Policy_Brief_Improving_Police_Response_to_Sexual_Assault.pdf.

106 See Janine Zweig & Martha Burt, Effects of Interactions Among Community Agencies on Legal System Responses to Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault in STOP-Funded Communities, 14(2) Crim. Just. Pol’y Rev. 249-72 (2003).

107 See Marilyn Strachan Peterson, et al., California SART Report: Taking Sexual Assault Response to The Next Level – Research Findings, Promising Practices & Recommendations, California Clinical Forensic Med. Training Ctr. 101 (Jan. 2009), http://www.calcasa.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/SART-Report_08.pdf (highlighting the importance of the participation of SART members, particularly law enforcement and prosecutors, in community education and outreach efforts to encourage victim reporting and inspire trust in the criminal justice system).

108 Please refer to your state’s specific ethics rules regarding public statements, in addition to reviewing the American Bar Association’s professional standards for further guidance. See Criminal Justice Standards, Prosecution Function (Am. Bar Ass’n, 4th ed. 2015).

109 For additional guidance on developing a public communication strategy, see RTI International, Sexual Assault Kit Initiative (SAKI) Media Relations: Key Considerations for Partnering with the Media, available at https://www.sakitta.org/resources/docs/SAKI-Media-Relations-Key-Considerations-for-Partnering-with-the-Media.pdf.

110 Amanda J. Waters & Lisa Asbill, Reflections on Cultural Humility, Am. Psychological Ass’n (Aug. 2013), http://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/newsletter/2013/08/cultural-humility.aspx (last visited Mar. 19, 2017).

111 See Waters & Asbill, supra note 110.

112 See, e.g., Nat’l Children’s All., Standards for Accredited Members 16-18 (2017).

113 See, e.g., Nat’l Children’s All., supra note 112.

114 See, e.g., A Prosecutor’s Guide for Advancing Racial Equity, Vera Inst. of Justice, (March 2015), https://www.vera.org/publications/a-prosecutors-guide-for-advancing-racial-equity; and Identifying and Preventing Gender Bias in Law Enforcement Response to Sexual Assault, Dep’t of Justice (Dec. 2015), available at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/file/799366/download. Although this assessment is important in all cases, it is particularly relevant in the response to victims sexual and intimate partner violence.

115 See Zweig & Burt, supra note 106.

116 See, e.g., Lisa Frohmann, Discrediting Victims’ Allegations of Sexual Assault: Prosecutorial Accounts of Case Rejections, 38(2) Social Problems 213-26 (May 1991); Frazier & Haney, supra note 44; Spohn & Tellis, supra note 16; Megan A. Alderden & Sarah Ullman, Creating a More Complete and Current Picture: Examining Police and Prosecutor Decision-Making When Processing Sexual Assault Cases, 18(5) Violence Against Women 525-51 (2012); Sharon Murphy, et al., Exploring Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Adult Female Sexual Assault Case Attrition, 3(2) Psychol. Violence 172-84 (2013); Sofia Resnick, Why Do D.C. Prosecutors Decline Cases Frequently? Rape Survivors Seek Answers, Rewire (Mar. 11, 2016), https://rewire.news/article/2016/03/11/d-c-prosecutors-decline-cases-frequently-rape-survivors-seek-answers/; Pattavina, Morabito & Williams, supra note 18; Melissa Schaefer Morabito, et al., It All Just Piles Up: Challenges to Victim Credibility Accumulate to Influence Sexual Assault Case Processing, Interpersonal Violence, 1-20 (2016).

117 See The Sexual Assault Kit Initiative, Sexual Assault Kit Initiative, https://sakitta.org/about/ (last visited May 22, 2017); Rebecca Campbell, et al., supra note 15; Why the Backlog Exists, End the Backlog, http://www.endthebacklog.org/backlog/why-backlog-exists (last visited May 22, 2017).

118 See, e.g., id. Sexual Assault Kit Initiative, supra note 117; David Lisak, Understanding the Predatory Nature of Sexual Violence, 14(4) Sexual Assault Rep. 49-64 (Mar./Apr. 2011), available at www.middlebury.edu/media/view/240951/original/.

119 Prosecutors should work with experts to understand the theory underlying the neurobiology of trauma, although expert testimony on this topic may not be appropriate for trial. Contact AEquitas to discuss further, at (202) 558-0040 or info@aequitasresource.org.

120 See AEquitas, Introducing Expert Testimony in Sexual Violence Cases (webinar), available at https://aequitasresource.org/resources/.

121 See id.

122 Prosecutors should also be aware of the availability of U Visas for victims of sexual violence. For more information and training opportunities on U Visas, see The Nat’l Immigrant Women’s Advocacy Project, https://www.wcl.american.edu/impact/initiatives-programs/niwap/ (last visited June 13, 2017).